Domination in Formula 1 might feel familiar thanks to Red Bull and Max Verstappen at the moment, but the benchmark for such performance was set in 1988 by McLaren.

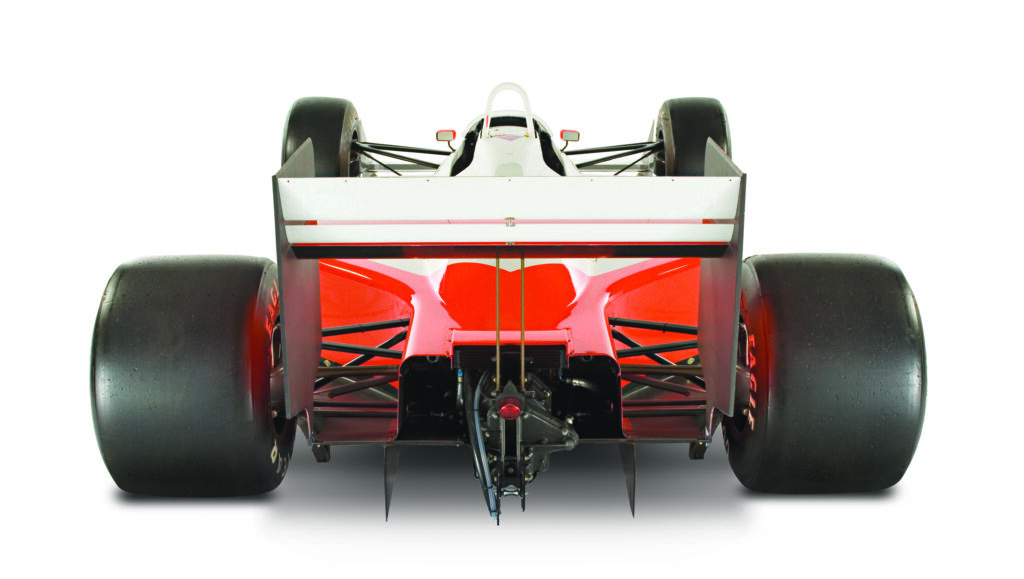

It won all but one race that year with the MP4/4 McLaren designed by Steve Nichols and a gifted team who would change the perception of what was possible in F1 at the time and into the future.

Nichols went to Ferrari with Alain Prost in 1990 and also worked for Jaguar’s ill-fated Formula 1 effort in the 2000s before becoming a design consultant.

He’s currently working on his own car – the Nichols Cars N1A – which blends the old and the new – and that should be ready later this year.

With such a diverse career, Podium Life asked Nichols about his experiences in the latest version of our recurring Q&A, ‘My Thoughts on Leadership’.

Who are some of your mentors? Who do you look up to?

I don’t know if ‘mentor’ is the right word but I’m always eternally grateful to Ron Dennis and John Barnard because they gave me the platform to start my career in Formula 1 (F1) all those years ago, and they’re remarkable people.

John was a great designer and taught me some valuable lessons. He put a lot of pressure on you to be your best, and his daring decision to design the MP4/1 with the original carbon fibre monocoque was a groundbreaking step in Formula 1 history. This marked a significant shift in the industry when you look at how many components are now made from carbon fibre on today’s F1 grid.

Ron [Dennis], too, deserves credit for backing John [Barnard] to use this new material.

In fact, the carbon fibre was so new and innovative that they couldn’t get anyone to make the monocoques for them in the UK or even in Europe.

However, I had an employment history with Hercules [Aerospace] in the USA, and I knew they wanted to expand the use of carbon fibre outside of the aerospace industry. So, I contacted my old colleagues and asked them if they were interested in a collaboration.

I thought it would be a perfect opportunity for them with the world exposure of F1. Subsequently, Ron [Dennis] and John [Barnard] quickly did the deal and it was a genuine revolution thanks to them.

Ron [Dennis] is a remarkable person in so many ways. He was a visionary, and he reshaped F1 by elevating marketing strategies, introducing advanced motorhomes and establishing sophisticated garage set-ups.

I remember things like the mechanics would have a specific layout in the factory with their benches, cabinets and tools all organised. This set-up would then be packed up and recreated at each racetrack.

My first interest in F1 dates back to 1962, to a magazine article called ‘Chapman’s Tubeless Wonder’ highlighting Colin’s masterpiece monocoque Lotus 25.

I found it such a beautiful design, and Colin became someone whom I looked up to at the time. Ultimately, it inspired me to become an F1 designer.

Sometimes people talk about their favourite racing cars, and I always think; mine are all Lotus!

I have both a 1962 Elite and a 1972 Elan. Although the later Lotus years were somewhat marred, Colin [Chapman] was someone whom I always respected for his designs and creativity.

Currently, I have huge respect for Adrian Newey, the best designer in F1 off all time in my opinion. You just have to look at the success he’s had at Williams and McLaren, and now Red Bull Racing – it’s just remarkable.

He seems to be able to put everyone else in the shadows. I know that at the beginning of the season, people were speculating that 2023 would be difficult for Red Bull but even with the cost cap penalty he has put them ahead.

Along the way, I’ve been fortunate enough to work alongside some very good other people, too. The McLaren design team, for instance, when John [Barnard] transitioned to Ferrari, were fantastic, and their contributions were invaluable.

What is the biggest lesson you have learned in motorsport?

The biggest lesson I learned was the value of teamwork. One of the most important things I’ve learned is to harness the team and take advantage of the brainpower.

You can only do so much with your two hands and brain, you need to involve the brainpower of everyone in the team. So, teamwork is perhaps the most important lesson of all.

What is the best piece of advice you’ve received?

Learning from John [Barnard], trying to attain perfection and trying to squeeze your brain to get the most out of yourself and then expanding on that to get the most out of the team you’re working with.

Try to seek perfection but remember that you cannot be perfect all the time, you need to learn when to back away and accept 98 per cent, otherwise, it can become a hindrance.

What book/article/film/podcast has best shaped your leadership style?

One interesting book I read was ‘The Art of Captaincy’ by Mike Brearley, it had some interesting ideas about leadership and teaches you how to lead a team.

It taught me that you need different techniques with various people, you can’t treat everybody the same.

Everyone has different personalities and it’s about suiting their abilities to an appropriate task. It’s about marrying up the qualities of the person and the job that would suit them best.

You’ve been a part of designing some of F1’s greatest cars. What are some of the challenges of leading the design process of an F1 car?

With Formula 1, it comes down to the design of the organisation as well as the design of the car. I think sometimes in modern F1, the organisations become complicated.

The teams are big, the technical side is much larger than what it was 20 or so years ago and that requires more management.

I think there should be three basic elements in the technical organisation of a Formula 1 team: mechanical design, aero design, and race engineering.

There are other parts also but those three elements have to work in perfect coordination, and you need to facilitate that coordination with one person in charge such as a technical chief or technical director, and they have to make sure things work the way they’re supposed to.

I know it’s quite often said that F1 is largely an aerodynamic formula, but that doesn’t mean the other sectors can be subpar.

The aero design, even if it’s the biggest part of the equation, is very much dependent on the mechanical design, with the mechanical design providing the platform that allows the aero concept to work.

You see that demonstrated quite dramatically over the last few years with the introduction of shaped floors and ground effect aerodynamics and how easy it is to get that wrong.

It also highlights how much it helps to have a deep understanding of the ground effect as witnessed by Adrian Newey’s dramatic success at Red Bull.

When I was Chief Designer at McLaren, it was important for me to get all those groups to work together, and we had to work together to get the best drivability we could from the aero.

Sometimes you can get a bit lost in the pursuit of maximum downforce and the aero becomes unstable, inconsistent and difficult to drive.

It’s better to have useful downforce, perhaps with a lower peak, making the car easier to drive, and giving the driver confidence so they can drive to the limit.

We introduced things like a longer wheelbase, anti-dive, anti-lift, anti-squat and rising front suspension geometry to try to minimise the movements of the car and therefore be able to control the pitch sensitivity of the aero.

So, it’s important that the mechanical design team, race engineering, and the aero team work together to make the aero concepts and the mechanical setup into an integrated package that will deliver the best possible performance.

The challenge of that organisational concept I described is to make it work. Dealing with the people and making them understand the integration is very important.

Efficiency is key; you need it everywhere. A single genius can only take you so far, but a great team can take you so much further.

If you get those people where they’re all working together, they respect each other, they like each other, and they are all pulling in the same direction, then it works amazingly well.

Even if you have a huge budget, it’s still important to be financially efficient too. Organising the human resources, the material resources, the financial resources, keeping on track with the time frame, and understanding the regulations well – it’s pretty complex stuff to deal with.

Now you’re a car constructor working on the N1A. Blending the classic and the new all into one package must have its challenges?

Yes, the N1A did have its challenges. When you look at this car, it’s certainly a blend of modern and classic.

The key examples of the retro aspects are present in the body, taking styling cues from 1960s Can-Am cars. This is combined with modern aspects, such as the bonded aluminium chassis developed by Stalcom and a Graziano transaxle gearbox, the same one used in the Audi R8, which has been strengthened and modified to suit the revs of the engine.

The engine in the N1A is a Chevrolet LS engine, a big banger American V8, harking back to the type of engines used in the 1960s Can-Am cars.

The engine is highly developed and features an all-aluminium engine block and heads. It is light, powerful and efficient (even from a financial point of view), making the N1A exceptionally fast.

We tried to combine all aspects of a great track car where you can take advantage of its motorsport DNA on both road and track. We tried to make it as fun as possible without being dangerous to drive. It’s a car that feels most at home on the circuit, and you can exploit the performance of the car and have a good time.

Bringing it all together has been difficult; we’re a very small company and we haven’t had a lot of financial backing so that’s slowed the process down. We use some of the same suppliers that supply parts to Formula 1 teams and because of that we get pushed aside when it comes to priority – it’s been a long process to get to where we are today.

The gear lever in the prototype is the same one [Ayrton] Senna used to win the 1992 Monaco Grand Prix, and the production models will have a gear lever inspired by this part. There are not many electronics to detract from the driving feel, but there will be traction control and anti-lock brakes to give drivers a helping hand.

In the past, when working in F1, I’ve come across technical chiefs who felt like they needed to know more about everyone’s job than they did, but I always thought the opposite.

I wanted them to know more about their area of expertise than I did. My job was to meld that all together, in the right proportions, bringing together experts to make the car as good as it could be.

I’ve used the same procedure with the N1A, for example using Stalcom to develop the monocoque and Richard Hurdwell for the suspension geometry.

In our initial prototype, we tested some of the concepts working with Gardner Douglas. They’ve been producing cars for a long time now and are particularly good with their Cobra cars. They produce very nice products, and that initial prototype was a big help in getting the N1A on the road today, despite the final product being quite different.

What’s the latest on the N1A and when it might be available?

The car is pretty much finished.

We started the engine last week and it’s going through its final mapping process. We’ll be doing a shakedown run soon and we already have parts for the first few customer cars in process.

The N1A is a bit old school. We wanted to achieve a retro feel and eventually, we might do a paddle shift variant, too. Watch this space.

With this being our first product, we are expecting production to begin in the last quarter of 2023.

What does the future of racing look like to you?

Well, I’m not fond of the current F1 cars, they’re big and heavy and they’ve got quite a few aero problems regarding the cars’ ability to race. I think they need to be more radical in their approach and need to go further in that direction to make them race better.

Saying that, I think the current cars are still technological marvels, they’re so sophisticated. With nearly 50 per cent thermal efficiency, that’s incredibly impressive, but from a financial point of view, I’m not sure it’s the best thing for the sport.

I’m not a huge fan of electric cars, they’re not as green as many think.

I think that perhaps the way forward for racing cars, at least, unless there’s a huge shift in battery technology, is to have simpler internal combustion engines with sustainable synthetic fuels, much like what Porsche is doing, and Paddy Lowe, who also worked in F1, with Zero Petroleum. I tend to think that’s the way forward.

When you look at the current battery technology, there are a few issues with sourcing lithium and various rare metals, not to mention the harm it does to the environment, so synthetic fuels might be the way forward for a long time.

I would like to see the cars much smaller and lighter. I don’t understand what they’ve done to the cars over the last few years.

However, from what I understand, they’re trying to minimise the wake of the cars. What they’ve actually done is made it worse, with wider cars, wider tires, wider and lower rear wings and adding downforce.

There should also be a lot of focus on efficiency and safety, and the future will hopefully include fully enclosed wheels and cockpit design.

The halo is a significant advancement in safety, sure, but small parts can still be a problem, so it still holds the conversation open for closed cockpits.

This should be developed in the interest of safety and I think the design of the cars will need a dramatic shift. I think the FIA [Federation Internationale de l’Automobile] needs to adjust its plans for future regulation changes to be completely different to what we have currently.

Pictures courtesy of McLaren Racing and Nichols Cars