Formula One predates the first curious device that could be referred to as a video game by at least eight years. Maybe that’s why almost as soon as we could display graphics on a screen there’s been some interpretation of F1 in video game form, gradually increasing in graphic fidelity as gaming hardware pressed on through the ages.

By the mid-to-late ‘80s, motorsports games were racing to achieve true 3D. Sega’s Hang-On (1985) and Outrun (1986) brought something like three-dimensionality to racing games thanks to Sega’s patented Super Scaler technology that made trees and signs smoothly grow in size as players approached them. On home consoles, games like 1987’s Highway Star (better known in the West as Rad Racer) simulated three dimensions with either the Japan-exclusive Famicom 3D System (a fancy pair of 3D glasses) or in the West, a pair of red and cyan anaglyph 3D glasses (much less fancy and much more made of cardboard).

In 1990, Nintendo added new depth to the quest for a three-dimensional racer with the introduction of Mode 7, a graphical mode that both the Super Famicom and its Western counterpart, the Super NES, that allowed an image to turn and scale in the background. All of a sudden, tracks could twist and turn realistically, achieving the illusion of navigating a three-dimensional space. This was used to great effect to breathe life into racing games such as F-Zero (a Super Famicom/Super NES launch title), Super Mario Kart (1992), and a pair of lesser known 16-bit titles based around Formula One, F1 ROC: Race of Champions (1992) and F1 ROC II: Race of Champions (1993) also known as Exhaust Heat and Exhaust Heat II in Japan and Europe.

F1 ROC: Race of Champions follows the 1992 Formula One season, with a set of races spanning the globe. F1 ROC II: Race of Champions changes things up by having players grind their way from Group C to Formula 3000 before finally competing in Formula One.

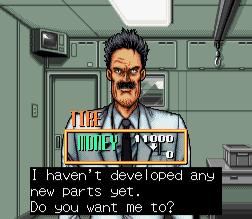

Both games feature a system for upgrading your machines by exchanging a variety of parts including your engine, tires, wings, and more. In the sequel, the engineer is a delightfully anime-looking guy in a lab coat who looks like he’s in need of a pit stop and has no problem griping at you when the R&D money isn’t flowing. You’ll need all the upgrades you can get too, because the competition is steep for podium placement.

In its review of Exhaust Heat, Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu compared the game to F-Zero, Nintendo’s futuristic hover car racer that beautifully demonstrated the potential for Mode 7 when it launched alongside the Super Famicom in late 1990. The comparison is spot on if not understated. Should the vehicles roaring down the track of F1 ROC II: Race of Champions suddenly be replaced by hover cars, I’m not convinced anyone would notice. And the hover car feel is there too, with cars slipping and sliding a bit more like they’re skating across glass than peeling rubber on an asphalt raceway.

If these two 16-bit racing titles are remembered as F-Zero with a Formula One-inspired paint job, I’d say they’ve done alright for themselves. Video game history is littered with the debris of racers long since forgotten by those that once played them, and undiscovered by those who came later. Still, looking back at the history of Formula One as interpreted by video game consoles through the generations, is to view the march of video game progress itself. F1 ROC I and II may be a brief pit stop on that race toward truly three-dimensional racers, but the stop is a fun one.