By the time Cruis’n USA made its N64 debut, Sony, Sega, and Nintendo had already chosen their respective racing game lanes. Namco’s Ridge Racer (1993) emerged as a graphical showcase of Sony’s debut home console, the PlayStation. A port of Sega’s Nascar-inspired Daytona USA (1994) arcade game became a launch title for the Sega Saturn in Western markets. Both games emphasized a level of realism that set them apart from previous racing titles.

With Cruis’n USA, Nintendo put forward a racing game that blended modern, polygonal graphics with a gameplay style more reminiscent of legacy racing games from the eight and sixteen-bit eras. The tracks were abstractions of the locations they were meant to represent, not recreations of actual raceways. Cruis’n kept things simple. Nothing got in the way of dropping players into action as quickly as possible so they could slam down the pedal and go.

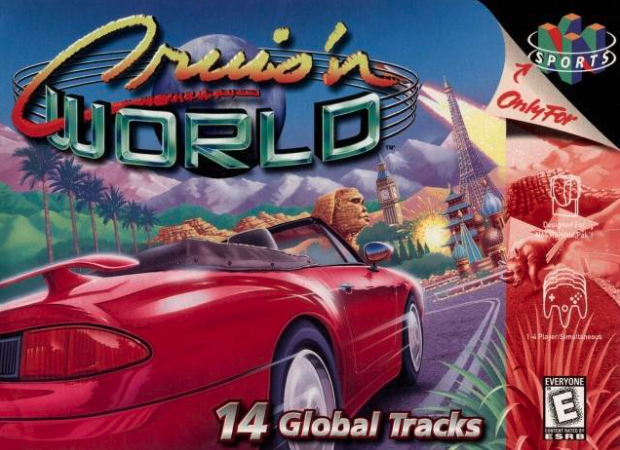

Two years after USA hit the arcade, a Cruis’n sequel emerged that would maintain the simplistic gameplay of the original, opting instead to keep things fresh with a series of new tracks based on locations (mostly) outside the continental U.S. Cruis’n World took drivers to Japan, Egypt, and Moscow, eventually culminating with a race in the wilds of Florida. The Nintendo 64 version of World added a final race around the moon.

Once again, Cruis’n World featured drivable vehicles with legally distinct names despite very obviously being real-life cars. Instead of a Volkswagon Beetle, there was the Scarab. A 1996 Dodge Viper became, simply, Serpent.

And driving this collection of cars in a low-gravity race around Earth’s nearest satellite is but one way that World defied the laws of science. The second Cruis’n game upped the ante on wackiness with the ability to perform sick stunts. For the first time in the series, racers could double tap the gas pedal to pop a wheelie or perform airborne flips by speeding over a ramp, earning both a few more precious seconds on the clock and the inherent joy that comes from piloting an inherently uncrashable vehicle in defiance of the laws of nature.

But the sick stunts and wild locales featured in World were only the beginning. Like an action movie franchise expanding its pyrotechnic budget for each additional installment, a third Cruis’n game had nowhere to go but bigger. Dropping all pretense of realism, Cruis’n Exotica hit arcades in 1999 with an entirely new collection of races including the lost city of Atlants, a dinosaur-infested Amazon jungle, and the surface of Mars.

Cruis’n Exotica hit arcades in 1999 with a follow up on the Nintendo 64 in 2000, completing a trilogy of Cruis’n games for Nintendo’s fifth generation console. In another first for the series, Exotica also received a port on the GameBoy Color that does manage to resemble the arcade game (at least in spirit) if you squint a bit.

The core gameplay of going fast, avoiding other cars, and trying to beat the clock, remained intact for Exotica, which instead added the ability for players to choose zany avatars including a martian, a cowboy, and a baby—because the only thing crazier than a cowboy driving a car is a baby driving a car.

It doesn’t take a pixelated, bikini-clad lady waving a flag in your face to see that the trilogy of Cruis’n games developed a clear trajectory over the initial trilogy of games. Where its contemporaries looked to recreate the thrill of motorsport on home consoles and the arcade, Cruisn’ wanted to give racers the thrill of popping a wheelie in a Volkswagon Kombi being driven by a space alien—a trajectory that leads directly to the kaiju-sized Yeti attacks and constant vehicular flips of the the most recent entry in the series, Cruis’n Blast. There is a certain simplistic charm to the original Cruis’n trilogy of games that make them both a memorable part of the Nintendo 64 library and an important (if wacky) step in the evolution of racing video games.